- Home

- Tyrese Gibson

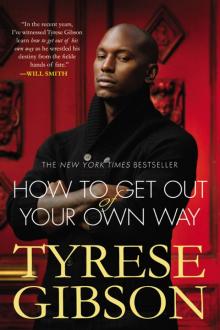

How to Get Out of Your Own Way Page 5

How to Get Out of Your Own Way Read online

Page 5

But I wasn’t with Gayle all the time. I still lived in Watts and went to the private school. By this point I had moved on to ninth grade in the high school section.

The principal was a kindhearted white man who I could tell cared about each and every student at the school. His door was always open, and he gave me his home and cell phone numbers in case I ever needed help. He was a good role model for me in the midst of all the chaos of school and my home. I could tell he understood the complexities of life that his students faced. He was honest and went the extra mile for me. Thinking back on it, he was the first white person who had ever cared for me, and I count him as the person who broke down my own personal color barrier. Up to that point, the only white people I had ever seen in my neighborhood were police officers, firefighters, doctors, or those guys who check electric meters. Of course, none of those people actually lived where we did. It was just the Latinos and us, for the most part, so I never experienced anyone outside of my race caring about me. But after I met him, I never saw color. I just saw people.

I remember being a little scared to go to high school, but I continued to use my power to win over people who should have been my enemies. Since I wasn’t banging, I wasn’t trying to be hard and gangsta like everybody else, and I figured if I was funny and got everybody laughing, nobody would try and beat me up or mess with me. If you’re not a threat, nobody will try to take anything from you—you’re harmless. And, for the most part, it worked. My humor became my strength against a lot of these realities, including the feeling that I was never going to get out of that damn school.

I did try to maintain a positive attitude but I still got into fights. They were a way of channeling my anger at being extremely scared and freaked out about the things I couldn’t control in my life. I had no control over what was going to happen at my house, or my day or night, but I had to go home because that’s where I lived. It was completely in their hands and that drove me nuts.

Some time in the early part of ninth grade I got into a big fight with one of the teachers who beat me up really bad. I came home with bruises on my face and knowing nothing would happen or change, I called the police on the school. By doing that I became a threat, because I could potentially expose what some of the teachers were doing to the kids, and they kicked me out. At the end of the day, I had such a history of fights like most of the kids there, so even if I had tried to go full-on and get a lawyer, nothing would have happened, because back then the school was for kids with behavioral problems.

I had been up for dual enrollment in high school as well, but I never made it because I was too bad and dysfunctional. So they never allowed me to go to public school for even half a day. Once I got kicked out of the behavioral school and knew I’d be going to Locke High School I didn’t think I’d be able to stay out of trouble. When I first arrived at Locke’s big campus, I thought I was so bad that I couldn’t believe they even allowed me to check in. I remember standing in the office with my moms, praying they would let me in, and being totally shocked when they let me register. I remember thinking, What do you mean, I can go straight back into public school?! I had been kicked out of public elementary school when I was young, went to a private school and got kicked out of there, too. My record was even worse than before I had left public school in the first place. I felt like I had two strikes against me, so it seemed crazy to me that they let me right back into public school. And because many of my former teachers had made me believe I wouldn’t make it in public school, I was worried I wouldn’t be able to survive at Locke.

But I was fine. It was like I was out of jail and able to be among society, and everything that some of the teachers at private school had told me I was or wasn’t ended up being the total opposite. There were kids at Locke High School who were bad as hell but that wasn’t me. I was on my p’s and q’s. For the first five or six months I was making good grades, going through the typical awkward stage of getting acquainted. Once I got comfortable, I started being my usual self—cracking jokes, acting all silly and funny, making friends, being the center of attention. I had always thought that the world was my stage and all of a sudden, my stage had gotten bigger. Sure, I still got into some trouble for skipping class, running in the hallways, putting up graffiti and getting into minor fights, but mentally I was in a better place.

I was able to interact and learn and readjust myself to being around regular folks and doing regular things. And I was finally able to make use of my talent. The first class I signed up for was music with Reggie Andrews. I went straight into his classroom on the first day of school and got into a friendly competition with my boy Timothy Jackson and we ended up just singing all the time. I could finally channel my energy in a good way and make use of my love for singing and songwriting. I was learning music and how to play the piano and drums.

Every morning I was desperate to get to school. I loved going because it was where I could eat, and for six or seven hours I was able to forget the reality of what went on in my house. I still hustled quarters and did odd jobs, because I needed change to take the bus to school in the morning. On the mornings I didn’t have change for the bus, I missed Angie picking me up even more.

In LA, when I was a kid, there were two types of buses. There was the RTD, which took you farther, but cost $1.10 each way. Then there was the DASH bus, which covered less ground, but was only twenty-five cents. On top of that, the RTD was more sophisticated. It had an automated change counter, which showed the bus driver how much money you put in. The DASH only had a metal tray that you tossed change into, and sometimes just the sound of coins clinking in the tray was enough to satisfy the driver and get you on board.

The problem was, on many days I didn’t have a single coin to clink in the tray, and on those mornings I would get a crick in my neck from looking for change on the ground as I walked to the bus stop. Fortunately, there was one driver who always let me on the bus whether I had the fare or not. But she was only one of many drivers on my route, and on the mornings I didn’t have any money I would have to get to the bus stop really early to catch her, because the other drivers would slam the door in my face when I told them I didn’t have any money. It was either that, wait more than an hour for her to circle the route and get to school late, or walk the three miles to school. Considering where I lived, I would have had to walk through at least ten to twelve different gang territories to get to school and that wasn’t always a comfortable thought.

I would wake up early and walk to the bus stop at 103rd and Success Avenue. Directly behind the stop was a giant tree, with branches that hung over the sidewalk and above the street. I would stand at the stop, squinting through the sun to see the early-morning bus coming down the street toward me, trying desperately to make out if my lucky driver was behind the wheel. The sun was usually so bright that I couldn’t make out who the driver was until a few seconds before the bus pulled up to the curb. If I was out of luck, the doors would swing open, and I would just stand there, head hanging in shame as the driver asked me if I was getting on. When I’d tell him that I didn’t have any money, he would close the doors without saying anything, leaving me on the curb. As it pulled away, the bus would scrape the branches of the tree behind me, so its leaves would fall to the ground. Then the bus engine would blow out a plume of exhaust, making the dust and the dirt and the leaves shoot up from the ground in the direction of anyone sitting at the bus stop. I would sit back on the bench and wait to reenact that same scene until the second angelic bus driver in my life showed up.

I would think, Getting to school should not be harder than school itself. No wonder there are so many dropouts. When it’s this difficult, how do they expect kids to show up? I wanted to go to school and get an education, I didn’t want to be a dropout. All I wanted was to escape the pain that was waiting for me back home, but the public transportation system was making that impossible. I had to miss school a few days because I couldn’t get a ride or hadn’t slept the night before. No child

should miss school because they can’t get there. And there I was, standing at the bus stop, not banging, not dope-slinging, not shooting, and not killing, I was just trying to get to school and I didn’t have a quarter. Twenty—five pennies. My thinking was, I’m a good person. I’m not a killer. I’m not crazy, I never went to jail. I’m just in the hood, so why am I struggling this hard? You would think that because you’re a good person in the midst of all this madness that things would be better for you. And then you see the dope dealers driving up the street in their nice cars with a loud sound system and girls in the front seat. You know they have on the latest Nikes and the fresh white T-shirts and the jewelry, and the cell phones. Waiting for the bus, trying to get to school, you can’t help but think, Man, if I start doing some of the shit that they’re doing then maybe I’ll get some of the money they’re getting. Because trying to do it the right way is just not paying off fast enough. That’s why most of the cats in the hood jump off into the dope game. But I didn’t want to gangbang—there were too many people dying and I didn’t want to die. And I loved going to school.

I found out after I arrived at Locke that there was a great musical tradition there. Reggie Andrews, my teacher, inspired me—he fed me when I was hungry and he was a father figure because he gave me advice on some of the stuff I was dealing with at home. He was my sounding board. Reggie was also a well-known producer. He had written “Let It Whip,” a hit song made famous by the Dazz Band, and many famous musicians had graduated from my school: Rickey Minor, a bass player and one of the most famous music directors in the country; Patrice Rushen, who sang “Forget Me Nots”; Gerald Albright, the saxophone player; and the whole trumpet section from Earth, Wind & Fire. All these legends went to my high school. The music department at Locke was a testament to Reggie Andrews being a great teacher.

Because of that tradition, one day some folks called my high school and said they were looking for a male black kid for a national Coke commercial. Since I was sixteen, about the age of the kid they wanted, Reggie told me about it. I didn’t have money to take the bus across town to get to the audition, so Reggie said he would take me himself. I just had to wait for him to finish teaching and lock up the music department. When we finally got to the audition, we were almost three hours late. The woman running the auditions was still there, but she was all packed and ready to go; she was just waiting for her ride, who was stuck in traffic. When I asked her if I could still sing for her, she was very cold and firm and said, “You’re late, I’m sorry.” I started apologizing to her, explaining that I didn’t have a ride, and Reggie backed me up, telling her that we were late because I had to wait for him, that I was from the hood and didn’t have money for transportation, otherwise I would have been there earlier. She sympathized with me and with an attitude, sighed and said, “All right, just warm up.”

I started singing and she looked at me with her eyes lit up. She started unpacking her equipment; she pulled out a camera, gave me a pair of headphones, and put a backpack on me. I sang Montell Jordan’s “This Is How We Do It” so I could dance while I was singing, and then I did two or three of my favorite songs. She asked me to improvise some Coca-Cola jingles, and as I did I was smiling and laughing—I was doing pretty much whatever she asked me to do, and then some.

She told me I was amazing, but I didn’t know what that meant because it was my first audition. I had extremely low expectations because up until that point in my life, the major things I had tried to do had not happened on any level. I wanted a record deal, but people kept turning me down or weren’t returning my phone calls. I was excited that I had been able to audition, but I was still negative about it. I didn’t really believe that the woman was really going to show the tapes of my audition to her associates. I knew it would be a national commercial, I knew they had auditioned kids in all the major cities, and that Los Angeles was the last location and I was literally the last person to show up. I didn’t believe it would happen for me. As Reggie drove me home, he kept telling me that I had done a great job, but I was thinking there was no way they would choose me for it. Now that I’ve gotten older I am able to see that it was all a part of God’s plan. Four days later I found out I got the gig. The commercial was a hit and got such a great response that they took it international.

Years later, I realized how crazy it was that in the commercial that sparked my career I was singing on a bus—a bus just like the one I had to take every day, a bus I usually couldn’t afford, that represented many of my childhood struggles. Because of that commercial, I never had to take the bus again.

I don’t usually talk about my childhood because it’s mostly bad memories. I don’t want to sit up and be reminded of all this stuff that I love to forget, because you can’t get points today for yesterday’s game—whatever happened yesterday is over. Today is a new day. So many people are submerged in what was, they don’t even focus on now. They don’t focus on the future. Every time they look back they cry and have all this pain about their past.

I know that the dysfunction I was exposed to as a child made me who I am. I like to say that every lesson is a blessing. I don’t think I would be this passionate about life, and I don’t think my work ethic would be the way it is, if my childhood had been nice and peaceful. It wouldn’t have created the motivation in me to want something different for my life.

I use my messed-up childhood to keep me motivated and to keep my life and career moving forward because I know that hell is out there. I don’t sit around and dwell on my past, and that way I’m able to get out of my own way, because to hold on to the past limits your future. I’m using my past as a part of my determination to never experience my past again.

Chapter 2

How Much Do You Love Yourself?

This book is called How to Get Out of Your Own Way, and I want you to really think about that for a minute. What does that mean to you? Have you ever let opportunities pass you by because you didn’t think you were good enough or worthy enough to take them? Have you ever allowed others to prevent you from improving your life? Have you ever stopped yourself from sorting out a problem? Most of the things that I’ll be speaking about are adjustments I’ve made in my own life, things that I’ve been able to see and recognize and stop doing. You can get in front of your problems and get in control of your life and make it better. Hopefully something you read here will give you permission to want better for yourself, because getting to whatever that better spot is should be the ultimate mission of your life.

The one mission I had when I was young was to get out of the hood. I decided that I wanted better for myself and that I didn’t want to be like anybody around me. I wanted my life to be the complete opposite of everything and most of the people I grew up around. I decided to fall in love with who I am. I didn’t know it, but even back then I was trying to get out of my own way.

There wasn’t a specific time or date or monumental moment when I knew I had to get out of there. For me, the process of getting out of my own way happens moment by moment. When each moment presents itself, I can decide to do something wrong—if I was already made aware that it was wrong—or I can do it right. When you know there are better circumstances you can be in, or that there’s a better way to do something, and you decide right then and there you want better for yourself and do it right, that’s when you’re technically getting out of your own way.

But it’s not as easy as that because your life decisions boil down to how you see yourself and how much you love and value yourself. Your actions reflect what you want for yourself and what you feel you deserve. I grew up with a few people who didn’t think they deserved anything and that’s the way some of them are still living. Everything I was doing when I was living in the hood shows how much I loved myself: I loved myself too much to keep living like that. I loved myself too much to not try and hustle for quarters for food or call every record label to get a record deal. You can think about this in all areas of your life: I love myself too much to date s

omeone like you. I love myself too much to keep sitting on my ass instead of searching for a new job. I love myself too much to have unprotected sex, or to keep friends in my life who bring me down.

We need to find out how much we love ourselves in order to get out of our own way. Part of that is accepting our flaws. It sounds contradictory, but you have to see the truth of who you are in order to get in front of the problem. How can you ever understand your actions and try to change until you take a good look at the choices you’ve made? How can you open up a line of communication with yourself or others about your actions and try to change? You have to figure out why you keep staying on the wrong path and making the wrong decisions.

One of my favorite quotes that really shook me up when I heard it was, “You’ll never know who you are till you discover who you’re not.” It made me feel more comfortable with accepting my flaws. How can I make any changes in my life if I’m not in tune with the way I feel about myself?

You have to come clean with yourself. You’ve got to be an open book. You’ve got to allow people to see into you and you’ve got to put all your flaws on the table, especially the things you don’t understand. You’ve got to be vulnerable and be willing to accept some of the worst things you could ever hear about yourself, especially if you’ve been messing up. This is something I went through myself and it was tough—like my whole world crashed in—but I’m a better man for it. When you start to look back and accept your bad choices along with the good, learn from them, and start to love yourself enough, you’ll begin to get in front of it and out of your own way.

How to Get Out of Your Own Way

How to Get Out of Your Own Way